Is it misfortune or not? I really cannot say - but fortune of some kind has made my path cross with that of the supernatural time and time again.

I know not why this should happen. I have had little training for this sort of thing - being but a humble lawyer. I would not say I am attuned to matters spiritual; no, my thoughts are rooted in the real world. I have feet of clay.

And yet it keeps happening. Why? I simply cannot say but every year or so - sometimes more often than that - I just run into another of these extraordinary events.

And some people appear to envy me this! They actually wish that it could happen to them.

"And have you ever seen a ghost?" they ask, simpering stupidly. And when I say "Yes of course I have," they say something like "OOOH ? aren't you lucky ?I'd love to see one" ?Blithering idiots!

A haunting is not a sideshow. It is not some music hall entertainment. Ghosts should not be there. When they intrude into our world it is wrong. That intrusion brings with it fear and horror and... sometimes, worse.

So why do I not refuse to look, to investigate, to peer into corners of a world that should not exist? Why do I not stay at home at my fireside, with my family and my books around me? Is this some opiate that has now infused into my senses? The moth has too little imagination to understand the risk that the flame entails. But that defence is not open to me. I can imagine, oh yes, I can imagine?. and yet each time I am asked for help I am pulled, as though I have some invisible internal magnet, drawing me inexorably to the next horrible, absorbing nightmare.

Have I seen a ghost?

Oh yes, - yes, - I have,,,

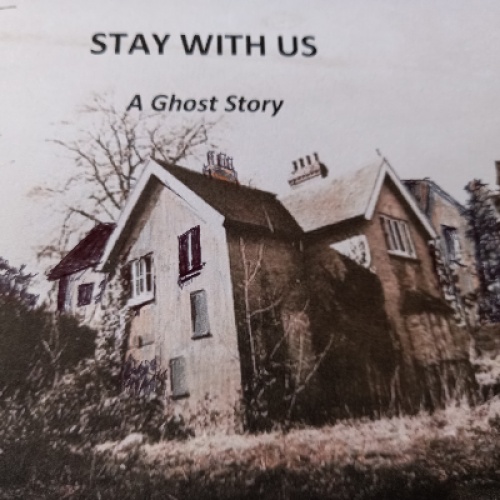

Let me take you to the village of Langdon. A pretty enough place. Cotswold stone, thatched cottages, duck pond, coaching inn?an idyllic rural setting. It so happened that an estate that I was taking to Probate included a farmhouse and outbuildings there, that had apparently lain deserted for some years.

The late owner, a widower for many years, had been committed to an asylum two or three years ago. It seems that he had left the farm many years earlier, but eventually was committed because of his screaming. I was told that whenever the curtains were closed he screamed until they were opened. The same happened whenever the light was turned off. Eventually the poor soul died screaming. No one knew why; he rarely spoke - he just screamed and ultimately, died.

Now a good, sizeable, complicated Probate is a wonderful thing. The assets have to be identified and then gathered in like a diverse but bountiful harvest. Then it must ripen like a good cheese, to mature like fine wine, to season like a baulk of sturdy timber. And, in the fullness of time, the assets must be valued? and so it was with this estate and with this farmhouse. I enquired of a well-known local valuer and property agent as to the value of this piece of real estate. Back came the suspiciously swift reply... "This property is not saleable".

Not saleable? Not saleable? This was unheard of. Already we were entering the realm of the unknown. An estate agent will put a price on anything. ? A flea-bitten farm dog - "This lively and valuable thoroughbred" ? a dung heap ? "This fertile and aromatic parcel of land" ? his own grandmother? "This sturdy farmyard animal" ? Not saleable? My curiosity was thoroughly engaged and when instructions from the executors were confirmed to go and investigate, I set off for Gloucestershire forthwith.

The inn, where I was eventually installed, was comfortable and well run. The village was charming. After a substantial dinner I walked out into pleasant evening sunshine to cast an eye over the property I had come to inspect. It stood alone, set back a little from a lane that led out of the village to, apparently, nowhere.

How desolate, even on a bright sunny evening, an empty ruined house can be. Is it foolish to ascribe feelings or character to a pile of bricks, mortar and timber? Is it wrong to describe a house, where the lights shine out and where music and laughter fill the air, as a happy house? All we are doing is to endow the building with the feelings of those who dwell there. In which case the ruin that I observed was desolate, because desolation itself dwelt there.

Rank weeds grew everywhere; bramble and ivy invaded the walls, pushing spiky fingers into crevices and doorways. Windows, some still glazed, others empty like the eye sockets of a skull, gazed bleakly at the surrounding decay.

As I stared, the sun sank out of sight behind trees from which the harsh call of rooks sounded. I felt a sudden chill and turned back, my spirits unexpectedly low, to the comfort of the inn.

A sound night's sleep and a hearty breakfast renewed my morale. When the landlord casually enquired of my business in Langdon and learned of my interest in the farmhouse even his sudden pallor and confused muttering as he hurried away did not dent my resolve. The local agent, when I visited him was more specific.

"If you take my advice, you will not go near that place. Under no circumstances should you go inside it".

When I asked him why not, he would only say that the place was full of death. He would be drawn no further but was adamant that I should not enter. As I left, clearly unimpressed by his warning, he took my arm and gruffly but with deep earnestness begged me to believe him. I gently removed his grip and said that he should not worry, I would be very careful where I trod, (I still thought he was talking about structural dangers) and strode off towards the target of my enquiries. I could feel him watching me as I went, and his anxiety and helplessness were almost palpable.

A storm was blowing up as I stumped off down the road and it seemed that even the wind that blew fiercely in my face was trying to stop me from reaching my goal. But I arrived and, suddenly unnerved, made a cautious circuit of the building to reconnoiter. The back disclosed upstairs windows with, curiously, steel bars behind half-open shutters. The back door was wedged open and after beating down shoulder high nettles with my walking stick, I entered a building that stank of decay, mould and damp. I could open none of the downstairs doors and began to ascend an open staircase that rose near the doorway through which I had just come. The timbers seemed sound enough, although they creaked horribly, and I arrived, still in one piece, at a long hallway with a door nearby leading to a rear facing room. I tried the door, expecting it to be as unyielding as the others, but to my surprise the handle turned, and the door opened smoothly and silkily.

I entered one of the rooms that was furnished with bars and shutters. It was a large room with a fireplace at one end, a few battered armchairs by it and what looked like a pile of rags in a far corner. On the mantelpiece was an oil lamp, with, it seemed, some oil left in it. As the shutters were partly closed and the day was gloomy anyway, it was difficult to see clearly, so I lit the lamp and looked around the room.

I do not know how to describe the feeling that swept through my being. I have felt it before; I may do so again although God knows I do not want to. It is a feeling that the room, or the place, is not right. There is something, or someone there that makes it very far from right. I felt it then, most strongly, overpoweringly. I knew I should not have gone into that room, or into that building, but I was there, in the middle of I knew not what. I just knew that it was wrong.

The light flickered and the shadows danced unpleasantly. I heard a noise in the room that for all the world was like leaves being blown around a courtyard. But there were no leaves and there was no wind inside that room. In case it was rats. and they were scurrying around the rags in the corner, I walked over to the pile and poked it with my walking stick. It met with more resistance than rags would have given. I moved part of the rags with my stick and saw to my horror a withered hand. Bending down I examined further and realised that what was before me was the body of a man, long, long dead, desiccated and wrapped in a tattered greatcoat.

You may find this hard to believe but I did not feel this corpse to be in any way the source of what was so unpleasant and oppressive in that room. I saw the dried-up withered face, with its look of weariness and utter horror and felt nothing but sorrow and compassion. In its other hand I saw, still clasped between finger and thumb, a piece of metal, perhaps a broken spoon handle, or something like that and noticed that there were deep scratch marks on the plaster in the corner where he lay. I brought the lamp nearer to them. Had this poor devil been trying to scratch through the plaster? No, it wasn't like that - it was writing. I crouched down nearer still to decipher it and eventually made it out. He had written "they will not let me out, they want me to stay".

I stood up and turned into the room to try to make sense of this and heard again the rustling noise. This time it clearly came across the room towards me in fact it surrounded me. The lamp seemed to dim although there remained plenty of oil. I felt unbelievably weary.

I was standing by an old armchair, and I sat down in it. Once seated, I looked around and, in the gloom, sensed, and then dimly began to see, figures, several of them, clustering round me. One, seeming slightly clearer than the rest, stooped over me and spoke to me in little more than a whisper. He, or it, said only three words, "stay with us" but said them with such terrible longing and hunger that it was loathsome and fearful.

They all began to whisper the same message, and I began to see their forms and their faces a little more clearly. There was no comfort in that. They were male and female, gaunt, in rags, grey of face and dress. And from their eyes and their expression it was all too easy to read that they hungered and thirsted desperately for me, for I was still alive, and they were not.

I summoned all my strength and stood up. I went to move towards the door and it slammed shut. Although the lock must have been rusted to a solid lump, the key turned within it. I forced my way, against invisible but powerful pressure, to the door but having reached it, could not turn the key at all. It was utterly immovable. I turned towards the windows. Barred though they were, perhaps I could shout for help. The shutters closed, not blown by a strong wind, they just slowly and deliberately closed and push against them as I might I could not open them an inch.

My heart was beating, hammering in my chest as panic gripped me. The figures gathered round me again and one of them, male or female, I have no idea, placed a grey hand on my forearm. It did not exactly touch me, but I felt, not on my skin or in my flesh but down in the very bone itself, a deep, deep ache, as though, (and this was the thought than ran through my mind at the time), this thing wanted me to feel the way it felt, all the time.

I suddenly realised that I was still holding the oil lamp. On impulse, I threw it at the door with all my might. It smashed and the oil covered the door with bright flame that ate greedily into the dry, old wood of the door, and of the frame, and then of the panelling on the wall around the door. I walked to the far side of the room, back to the armchair, ? I may even have sat down again. I was strangely calm at the approach of a death that was at least earthly. The fire was spreading across the room, the smoke hunting for ways out of the building, probably pouring out through gaps in the shutters into the fresh air. The figures stood still and apparently uncomprehending.

Apart from the spread of the flames, time appeared to stand still. It could only have been a minute or so before a crashing noise from the other side of the door signified that I was to be rescued and, indeed, the door began to disintegrate as blows rained down on it. The figures went past me and seemed to vanish, but the last one bent down and whispered to me as it went.

Into the room, puffing and coughing, crashed the old agent accompanied by a couple of farmhands. They pulled me through the burning doorway and helped me down the stairs and out into the sweetest air that I have ever breathed. I heard the agent say to his helpers "come on lads, let's try to put it out" but, gasping still for the smoke which I had breathed in, I said with all the strength I could muster "No, let it burn," and the agent said, "Aye, that's right, it should burn". And burn it did, all through the rest of the day and it smouldered all night by all accounts ?. but I was not there to see it.

Despite wheezing, coughing and stinking of smoke and singed hair, I left that afternoon on the coach to Gloucester and then on a night train back to London. And if you think that I had a moment's sleep on that journey you would be wrong. Just as you would be wrong if you think that I can ever go past an empty derelict house without feeling the horror of that hand on me and the deep ache in the bone of my forearm. And you would also be wrong if you thought that I have ever had a good night's sleep in the years which have followed, that I have ever forgotten the look in those hungry, grey eyes, or that I have ever forgotten the words that the figure whispered to me as it disappeared.

Do you ever wake up at night thinking that there is someone in your room? Do you ever screw up your eyes to try to penetrate the dark and do you ever think "is that a figure there?" ?. I do.

And I know that one night it won't be the shadow cast by an old wardrobe, or a curtain blowing at a draughty window, it will be something that I won't be able to bear but that I know will come, because the figure that whispered to me, as it left that burning room said? "We will come for you".