Suraj stood near the cutting, waiting for the mid-day train. It wasn’t a station, and he wasn’t catching a train. He was waiting so that he could watch the steam-engine come roaring out of the tunnel.

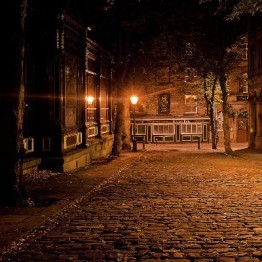

He had cycled out of the town and taken the jungle path until he had come to a small village. He had left the cycle there, and walked over a low, scrub-covered hill and down to the tunnel exit.

Now he looked up. He had heard, in the distance, the shrill whistle of the engine. He couldn’t see anything, because the train was approaching from the other side of the hill; but presently a sound, like distant thunder, issued from the tunnel, and he knew the train was coming through.

A second or two later, the steam-engine shot out of the tunnel, snorting and puffing like some green, black and gold dragon, some beautiful monster out of Suraj’s dreams. Showering sparks left and right, it roared a challenge to the jungle.

Instinctively, Suraj stepped back a few paces. And then the train had gone, leaving only a plume of smoke to drift lazily over tall shisham trees.

The jungle was still again. No one moved. Suraj turned from his contemplation of the drifting smoke and began walking along the embankment towards the tunnel.

The tunnel grew darker as he walked further into it. When he had gone about twenty yards, it became pitch black. Suraj had to turn and look back at the opening to reassure himself that there was still daylight outside. Ahead of him, the tunnel’s other opening was just a small round circle of light.

The tunnel was still full of smoke from the train, but it would be several hours before another train came through. Till then, it belonged to the jungle again.

Suraj didn’t stop, because there was nothing to do in the tunnel and nothing to see. He had simply wanted to walk through, so that he would know what the inside of a tunnel was really like. The walls were damp and sticky. A bat flew past. A lizard scuttled between the lines.

Coming straight from the darkness into the light, Suraj was dazzled by the sudden glare. He put a hand up to shade his eyes and looked up at the tree-covered hillside. He thought he saw something moving between the trees.

It was just a flash of orange and gold, and a long swishing tail. It was there between the trees for a second or two, and then it was gone.

About fifty feet from the entrance to the tunnel stood the watchman’s hut. Marigolds grew in front of the hut, and at the back there was a small vegetable patch. It was the watchman’s duty to inspect the tunnel and keep it clear of obstacles. Every day, before the train came through, he would walk the length of the tunnel. If all was well, he would return to his hut and take a nap. If something was wrong, he would walk back up the line and wave a red flag and the engine-driver would slow down. At night, the watchman lit an oil lamp and made a similar inspection of the tunnel. Of course, he could not stop the train if there was a porcupine on the line. But if there was any danger to the train, he’d go back up the line and wave his lamp to the approaching engine. If all was well, he’d hang his lamp at the door of the hut and go to sleep.

He was just settling down on his cot for an afternoon nap when he saw the boy emerge from the tunnel. He waited until Suraj was only a few feet away and then said: ‘Welcome, welcome, I don’t often have visitors. Sit down for a while, and tell me why you were inspecting my tunnel.’

‘Is it your tunnel?’ asked Suraj.

‘It is,’ said the watchman. ‘It is truly my tunnel, since no one else will have anything to do with it. I have only lent it to the government.’

Suraj sat down on the edge of the cot.

‘I wanted to see the train come through,’ he said. ‘And then, when it had gone, I thought I’d walk through the tunnel.’

‘And what did you find in it?’

‘Nothing. It was very dark. But when I came out, I thought I saw an animal – up on the hill – but I’m not sure, it moved away very quickly.’

‘It was a leopard you saw,’ said the watchman. ‘My leopard.’

‘Do you own a leopard too?’

‘I do.’

‘And do you lend it to the government?’

‘I do not.’

‘Is it dangerous?’

‘No, it’s a leopard that minds its own business. It comes to this range for a few days every month.’

‘Have you been here a long time?’ asked Suraj. ‘Many years. My name is Sunder Singh.’ ‘My name’s Suraj.’

‘There’s one train during the day. And another during the night. Have you seen the night mail come through the tunnel?’

‘No. At what time does it come?’

‘About nine o’clock, if it isn’t late. You could come and sit here with me, if you like.

And after it has gone, I’ll take you home.’

‘I shall ask my parents,’ said Suraj. ‘Will it be safe?’

‘Of course. It’s safer in the jungle than in the town. Nothing happens to me out here, but last month when I went into the town, I was almost run over by a bus.’

Sunder Singh yawned and stretched himself out on the cot. ‘And now I’m going to take a nap, my friend. It is too hot to be up and about in the afternoon.’

‘Everyone goes to sleep in the afternoon,’ complained Suraj. ‘My father lies down as soon as he’s had his lunch.’

‘Well, the animals also rest in the heat of the day. It is only the tribe of boys who cannot, or will not, rest.’

Sunder Singh placed a large banana-leaf over his face to keep away the flies, and was soon snoring gently. Suraj stood up, looking up and down the railway tracks. Then he began walking back to the village.

The following evening, towards dusk, as the flying foxes swooped silently out of the trees, Suraj made his way to the watchman’s hut.

It had been a long hot day, but now the earth was cooling, and a light breeze was moving through the trees. It carried with it a scent of mango blossoms, the promise of rain.

Sunder Singh was waiting for Suraj. He had watered his small garden, and the flowers looked cool and fresh. A kettle was boiling on a small oil-stove.

‘I’m making tea,’ he said. ‘There’s nothing like a glass of hot tea while waiting for a train.’

They drank their tea, listening to the sharp notes of the tailorbird and the noisy chatter of the seven-sisters. As the brief twilight faded, most of the birds fell silent. Sunder Singh lit his oil-lamp and said it was time for him to inspect the tunnel. He moved off towards the tunnel, while Suraj sat on the cot, sipping his tea. In the dark, the trees seemed to move closer to him. And the night life of the forest was conveyed on the breeze – the sharp call of a barking-deer, the cry of a fox, the quaint tonk-tonk of a nightjar. There were some sounds that Suraj couldn’t recognise – sounds that came from the trees, creakings and whisperings, as though the trees were coming alive, stretching their limbs in the dark, shifting a little, reflexing their fingers.

Sunder Singh stood inside the tunnel, trimming his lamp. The night sounds were familiar to him and he did not give them much thought; but something else – a padded footfall, a rustle of dry leaves – made him stand alert for a few seconds, peering into the darkness. Then, humming softly to himself, he returned to where Suraj was waiting. Another ten minutes remained for the night mail to arrive.

As Sunder Singh sat down on the cot beside Suraj, a new sound reached both of them quite distinctly – a rhythmic sawing sound, as if someone was cutting through the branch of a tree.

‘What’s that?’ whispered Suraj.

‘It’s the leopard,’ said Sunder Singh.

‘I think it’s in the tunnel.’

‘The train will soon be here,’ reminded Suraj.

‘Yes, my friend. And if we don’t drive the leopard out of the tunnel, it will be run over and killed. I can’t let that happen.’

‘But won’t it attack us if we try to drive it out?’ asked Suraj, beginning to share the watchman’s concern.

‘Not this leopard. It knows me well. We have seen each other many times. It has a weakness for goats and stray dogs, but it won’t harm us. Even so, I’ll take my axe with me. You stay here, Suraj.’

‘No, I’m going with you. It’ll be better than sitting here alone in the dark!’

‘All right, but stay close behind me. And remember, there’s nothing to fear.’

Raising his lamp high, Sunder Singh advanced into the tunnel, shouting at the top of his voice to try and scare away the animal. Suraj followed close behind, but he found he was unable to do any shouting. His throat was quite dry.

They had gone just about twenty paces into the tunnel when the light from the lamp fell upon the leopard. It was crouching between the tracks, only fifteen feet away from them. It was not a very big leopard, but it looked lithe and sinewy. Baring its teeth and snarling, it went down on its belly, tail twitching.

Suraj and Sunder Singh both shouted together. Their voices rang through the tunnel. And the leopard, uncertain as to how many terrifying humans were there in the tunnel with him, turned swiftly and disappeared into the darkness.

To make sure that it had gone, Sunder Singh and Suraj walked the length of the tunnel. When they returned to the entrance, the rails were beginning to hum. They knew the train was coming.

Suraj put his hand to the rails and felt its tremor. He heard the distant rumble of the train. And then the engine came round the bend, hissing at them, scattering sparks into the darkness, defying the jungle as it roared through the steep sides of the cutting. It charged straight at the tunnel, and into it, thundering past Suraj like the beautiful dragon of his dreams.

And when it had gone, the silence returned and the forest seemed to breathe, to live again. Only the rails still trembled with the passing of the train.

And they trembled to the passing of the same train, almost a week later, when Suraj and his father were both travelling in it.

Suraj’s father was scribbling in a notebook, doing his accounts. Suraj sat at an open window staring out at the darkness. His father was going to Delhi on a business trip and had decided to take the boy along. (‘I don’t know where he gets to, most of the time,’ he’d complained. ‘I think it’s time he learnt something about my business.’)

The night mail rushed through the forest with its hundreds of passengers. Tiny flickering lights came and went, as they passed small villages on the fringe of the

jungle.

Suraj heard the rumble as the train passed over a small bridge. It was too dark to see the hut near the cutting, but he knew they must be approaching the tunnel. He strained his eyes looking out into the night; and then, just as the engine let out a shrill whistle, Suraj saw the lamp.

He couldn’t see Sunder Singh, but he saw the lamp, and he knew that his friend was out there.

The train went into the tunnel and out again; it left the jungle behind and thundered across the endless plains; and Suraj stared out at the darkness, thinking of the lonely cutting in the forest, and the watchman with the lamp who would always remain a firefly for those travelling thousands, as he lit up the darkness for steam-engines and leopards.