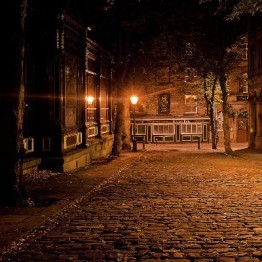

Whoo, whoo, whoo, cried the wind as it swept down from the Himalayan snows. It hurried over the hills and passed and hummed and moaned through the tall pines and deodars. There was little on Haunted Hill to stop the wind – only a few stunted

trees and bushes and the ruins of a small settlement.

On the slopes of the next hill was a village. People kept large stones on their tin roofs to prevent them from being blown off. There was nearly always a strong wind in these parts. Three children were spreading clothes out to dry on a low stone wall, putting a stone on each piece.

Eleven-year-old Usha, dark-haired and rose-cheeked, struggled with her grandfather’s long, loose shirt. Her younger brother, Suresh, was doing his best to hold down a bedsheet, while Usha’s friend, Binya, a slightly older girl, helped.

Once everything was firmly held down by stones, they climbed up on the flat rocks and sat there sunbathing and staring across the fields at the ruins on Haunted Hill.

‘I must go to the bazaar today,’ said Usha.

‘I wish I could come too,’ said Binya. ‘But I have to help with the cows.’

‘I can come!’ said eight-year-old Suresh. He was always ready to visit the bazaar, which was three miles away, on the other side of the hill.

‘No, you can’t,’ said Usha. ‘You must help Grandfather chop wood.’

‘Won’t you feel scared returning alone?’ he asked. ‘There are ghosts on Haunted Hill!’

‘I’ll be back before dark. Ghosts don’t appear during the day.’ ‘Are there lots of ghosts in the ruins?’ asked Binya.

‘Grandfather says so. He says that over a hundred years ago, some Britishers lived on the hill. But the settlement was always being struck by lightning, so they moved away.’

‘But if they left, why is the place visited by ghosts?’

‘Because – Grandfather says – during a terrible storm, one of the houses was hit by lightning, and everyone in it was killed. Even the children.’

‘How many children?’

‘Two. A boy and his sister. Grandfather saw them playing there in the moonlight.’ ‘Wasn’t he frightened?’

‘No. Old people don’t mind ghosts.’

Usha set out for the bazaar at two in the afternoon. It was about an hour’s walk. The path went through yellow fields of flowering mustard, then along the saddle of the hill,

and up, straight through the ruins. Usha had often gone that way to shop at the bazaar or to see her aunt, who lived in the town nearby.

Wild flowers bloomed on the crumbling walls of the ruins, and a wild plum tree grew straight out of the floor of what had once been a hall. It was covered with soft, white blossoms. Lizards scuttled over the stones, while a whistling thrush, its deep purple plumage glistening in the sunshine, sat on a window-sill and sang its heart out.

Usha sang too, as she skipped lightly along the path, which dipped steeply down to the valley and led to the little town with its quaint bazaar.

Moving leisurely, Usha bought spices, sugar and matches. With the two rupees she had saved from her pocket-money, she chose a necklace of amber-coloured beads for herself and some marbles for Suresh. Then she had her mother’s slippers repaired at a cobbler’s shop.

Finally, Usha went to visit Aunt Lakshmi at her flat above the shops. They were talking and drinking cups of hot, sweet tea when Usha realised that dark clouds had gathered over the mountains. She quickly picked up her things, said goodbye to her aunt, and set out for the village.

Strangely, the wind had dropped. The trees were still, the crickets silent. The crows flew round in circles, then settled on an oak tree.

‘I must get home before dark,’ thought Usha, hurrying along the path.

But the sky had darkened and a deep rumble echoed over the hills. Usha felt the first heavy drop of rain hit her cheek. Holding the shopping bag close to her body, she quickened her pace until she was almost running. The raindrops were coming down faster now – cold, stinging pellets of rain. A flash of lightning sharply outlined the ruins on the hill, and then all was dark again. Night had fallen.

‘I’ll have to shelter in the ruins,’ Usha thought and began to run. Suddenly the wind sprang up again, but she did not have to fight it. It was behind her now, helping her along, up the steep path and on to the brow of the hill. There was another flash of lightning, followed by a peal of thunder. The ruins loomed before her, grim and forbidding.

Usha remembered part of an old roof that would give some shelter. It would be better than trying to go on. In the dark, with the howling wind, she might stray off the path and fall over the edge of the cliff.

Whoo, whoo, whoo, howled the wind. Usha saw the wild plum tree swaying, its foliage thrashing against the ground. She found her way into the ruins, helped by the constant flicker of lightning. Usha placed her hands flat against a stone wall and moved sideways, hoping to reach the sheltered corner. Suddenly, her hand touched something soft and furry, and she gave a startled cry. Her cry was answered by another – half snarl, half screech – as something leapt away in the darkness.

With a sigh of relief Usha realised that it was the cat that lived in the ruins. For a moment she had been frightened, but now she moved quickly along the wall until she

heard the rain drumming on a remnant of a tin roof. Crouched in a corner, she found some shelter. But the tin sheet groaned and clattered as if it would sail away any moment.

Usha remembered that across this empty room stood an old fireplace. Perhaps it would be drier there under the blocked chimney. But she would not attempt to find it just now – she might lose her way altogether.

Her clothes were soaked and water streamed down from her hair, forming a puddle at her feet. She thought she heard a faint cry – the cat again, or an owl? Then the storm blotted out all other sounds.

There had been no time to think of ghosts, but now that she was settled in one place, Usha remembered Grandfather’s story about the lightning-blasted ruins. She hoped and prayed that lightning would not strike her.

Thunder boomed over the hills, and the lightning came quicker now. Then there was a bigger flash, and for a moment the entire ruin was lit up. A streak of blue sizzled along the floor of the building. Usha was staring straight ahead, and, as the opposite wall lit up, she saw, crouching in front of the unused fireplace, two small figures – children!

The ghostly figures seemed to look up and stare back at Usha. And then everything was dark again.

Usha’s heart was in her mouth. She had seen without doubt, two ghosts on the other side of the room. She wasn’t going to remain in the ruins one minute longer.

She ran towards the big gap in the wall through which she had entered. She was halfway across the open space when something – someone – fell against her. Usha stumbled, got up, and again bumped into something. She gave a frightened scream. Someone else screamed. And then there was a shout, a boy’s shout, and Usha instantly recognised the voice.

‘Suresh!’

‘Usha!’

‘Binya!’

They fell into each other’s arms, so surprised and relieved that all they could do was laugh and giggle and repeat each other’s names.

Then Usha said, ‘I thought you were ghosts.’ ‘We thought you were a ghost,’ said Suresh. ‘Come back under the roof,’ said Usha.

They huddled together in the corner, chattering with excitement and relief.

‘When it grew dark, we came looking for you,’ said Binya. ‘And then the storm broke.’

‘Shall we run back together?’ asked Usha. ‘I don’t want to stay here any longer.’ ‘We’ll have to wait,’ said Binya. ‘The path has fallen away at one place. It won’t be

safe in the dark, in all this rain.’

‘We’ll have to wait till morning,’ said Suresh, ‘and I’m so hungry!’

The storm continued, but they were not afraid now. They gave each other warmth and confidence. Even the ruins did not seem so forbidding.

After an hour the rain stopped, and the thunder grew more distant.

Towards dawn the whistling thrush began to sing. Its sweet, broken notes flooded the ruins with music. As the sky grew lighter, they saw that the plum tree stood upright again, though it had lost all its blossoms.

‘Let’s go,’ said Usha.

Outside the ruins, walking along the brow of the hill, they watched the sky grow pink. When they were some distance away, Usha looked back and said, ‘Can you see something behind the wall? It’s like a hand waving.’

‘It’s just the top of the plum tree,’ said Binya.

‘Goodbye, goodbye…’ They heard voices.

‘Who said “goodbye”?’ asked Usha.

‘Not I,’ said Suresh.

‘Nor I,’ said Binya.

‘I heard someone calling,’ said Usha.

‘It’s only the wind,’ assured Binya.

Usha looked back at the ruins. The sun had come up and was touching the top of the wall.

‘Come on,’ said Suresh. ‘I’m hungry.’

They hurried along the path to the village.

‘Goodbye, goodbye…’ Usha heard them calling. Or was it just the wind?

trees and bushes and the ruins of a small settlement.

On the slopes of the next hill was a village. People kept large stones on their tin roofs to prevent them from being blown off. There was nearly always a strong wind in these parts. Three children were spreading clothes out to dry on a low stone wall, putting a stone on each piece.

Eleven-year-old Usha, dark-haired and rose-cheeked, struggled with her grandfather’s long, loose shirt. Her younger brother, Suresh, was doing his best to hold down a bedsheet, while Usha’s friend, Binya, a slightly older girl, helped.

Once everything was firmly held down by stones, they climbed up on the flat rocks and sat there sunbathing and staring across the fields at the ruins on Haunted Hill.

‘I must go to the bazaar today,’ said Usha.

‘I wish I could come too,’ said Binya. ‘But I have to help with the cows.’

‘I can come!’ said eight-year-old Suresh. He was always ready to visit the bazaar, which was three miles away, on the other side of the hill.

‘No, you can’t,’ said Usha. ‘You must help Grandfather chop wood.’

‘Won’t you feel scared returning alone?’ he asked. ‘There are ghosts on Haunted Hill!’

‘I’ll be back before dark. Ghosts don’t appear during the day.’ ‘Are there lots of ghosts in the ruins?’ asked Binya.

‘Grandfather says so. He says that over a hundred years ago, some Britishers lived on the hill. But the settlement was always being struck by lightning, so they moved away.’

‘But if they left, why is the place visited by ghosts?’

‘Because – Grandfather says – during a terrible storm, one of the houses was hit by lightning, and everyone in it was killed. Even the children.’

‘How many children?’

‘Two. A boy and his sister. Grandfather saw them playing there in the moonlight.’ ‘Wasn’t he frightened?’

‘No. Old people don’t mind ghosts.’

Usha set out for the bazaar at two in the afternoon. It was about an hour’s walk. The path went through yellow fields of flowering mustard, then along the saddle of the hill,

and up, straight through the ruins. Usha had often gone that way to shop at the bazaar or to see her aunt, who lived in the town nearby.

Wild flowers bloomed on the crumbling walls of the ruins, and a wild plum tree grew straight out of the floor of what had once been a hall. It was covered with soft, white blossoms. Lizards scuttled over the stones, while a whistling thrush, its deep purple plumage glistening in the sunshine, sat on a window-sill and sang its heart out.

Usha sang too, as she skipped lightly along the path, which dipped steeply down to the valley and led to the little town with its quaint bazaar.

Moving leisurely, Usha bought spices, sugar and matches. With the two rupees she had saved from her pocket-money, she chose a necklace of amber-coloured beads for herself and some marbles for Suresh. Then she had her mother’s slippers repaired at a cobbler’s shop.

Finally, Usha went to visit Aunt Lakshmi at her flat above the shops. They were talking and drinking cups of hot, sweet tea when Usha realised that dark clouds had gathered over the mountains. She quickly picked up her things, said goodbye to her aunt, and set out for the village.

Strangely, the wind had dropped. The trees were still, the crickets silent. The crows flew round in circles, then settled on an oak tree.

‘I must get home before dark,’ thought Usha, hurrying along the path.

But the sky had darkened and a deep rumble echoed over the hills. Usha felt the first heavy drop of rain hit her cheek. Holding the shopping bag close to her body, she quickened her pace until she was almost running. The raindrops were coming down faster now – cold, stinging pellets of rain. A flash of lightning sharply outlined the ruins on the hill, and then all was dark again. Night had fallen.

‘I’ll have to shelter in the ruins,’ Usha thought and began to run. Suddenly the wind sprang up again, but she did not have to fight it. It was behind her now, helping her along, up the steep path and on to the brow of the hill. There was another flash of lightning, followed by a peal of thunder. The ruins loomed before her, grim and forbidding.

Usha remembered part of an old roof that would give some shelter. It would be better than trying to go on. In the dark, with the howling wind, she might stray off the path and fall over the edge of the cliff.

Whoo, whoo, whoo, howled the wind. Usha saw the wild plum tree swaying, its foliage thrashing against the ground. She found her way into the ruins, helped by the constant flicker of lightning. Usha placed her hands flat against a stone wall and moved sideways, hoping to reach the sheltered corner. Suddenly, her hand touched something soft and furry, and she gave a startled cry. Her cry was answered by another – half snarl, half screech – as something leapt away in the darkness.

With a sigh of relief Usha realised that it was the cat that lived in the ruins. For a moment she had been frightened, but now she moved quickly along the wall until she

heard the rain drumming on a remnant of a tin roof. Crouched in a corner, she found some shelter. But the tin sheet groaned and clattered as if it would sail away any moment.

Usha remembered that across this empty room stood an old fireplace. Perhaps it would be drier there under the blocked chimney. But she would not attempt to find it just now – she might lose her way altogether.

Her clothes were soaked and water streamed down from her hair, forming a puddle at her feet. She thought she heard a faint cry – the cat again, or an owl? Then the storm blotted out all other sounds.

There had been no time to think of ghosts, but now that she was settled in one place, Usha remembered Grandfather’s story about the lightning-blasted ruins. She hoped and prayed that lightning would not strike her.

Thunder boomed over the hills, and the lightning came quicker now. Then there was a bigger flash, and for a moment the entire ruin was lit up. A streak of blue sizzled along the floor of the building. Usha was staring straight ahead, and, as the opposite wall lit up, she saw, crouching in front of the unused fireplace, two small figures – children!

The ghostly figures seemed to look up and stare back at Usha. And then everything was dark again.

Usha’s heart was in her mouth. She had seen without doubt, two ghosts on the other side of the room. She wasn’t going to remain in the ruins one minute longer.

She ran towards the big gap in the wall through which she had entered. She was halfway across the open space when something – someone – fell against her. Usha stumbled, got up, and again bumped into something. She gave a frightened scream. Someone else screamed. And then there was a shout, a boy’s shout, and Usha instantly recognised the voice.

‘Suresh!’

‘Usha!’

‘Binya!’

They fell into each other’s arms, so surprised and relieved that all they could do was laugh and giggle and repeat each other’s names.

Then Usha said, ‘I thought you were ghosts.’ ‘We thought you were a ghost,’ said Suresh. ‘Come back under the roof,’ said Usha.

They huddled together in the corner, chattering with excitement and relief.

‘When it grew dark, we came looking for you,’ said Binya. ‘And then the storm broke.’

‘Shall we run back together?’ asked Usha. ‘I don’t want to stay here any longer.’ ‘We’ll have to wait,’ said Binya. ‘The path has fallen away at one place. It won’t be

safe in the dark, in all this rain.’

‘We’ll have to wait till morning,’ said Suresh, ‘and I’m so hungry!’

The storm continued, but they were not afraid now. They gave each other warmth and confidence. Even the ruins did not seem so forbidding.

After an hour the rain stopped, and the thunder grew more distant.

Towards dawn the whistling thrush began to sing. Its sweet, broken notes flooded the ruins with music. As the sky grew lighter, they saw that the plum tree stood upright again, though it had lost all its blossoms.

‘Let’s go,’ said Usha.

Outside the ruins, walking along the brow of the hill, they watched the sky grow pink. When they were some distance away, Usha looked back and said, ‘Can you see something behind the wall? It’s like a hand waving.’

‘It’s just the top of the plum tree,’ said Binya.

‘Goodbye, goodbye…’ They heard voices.

‘Who said “goodbye”?’ asked Usha.

‘Not I,’ said Suresh.

‘Nor I,’ said Binya.

‘I heard someone calling,’ said Usha.

‘It’s only the wind,’ assured Binya.

Usha looked back at the ruins. The sun had come up and was touching the top of the wall.

‘Come on,’ said Suresh. ‘I’m hungry.’

They hurried along the path to the village.

‘Goodbye, goodbye…’ Usha heard them calling. Or was it just the wind?