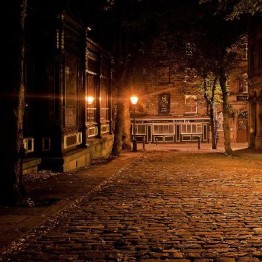

It was an old dilapidated building with vegetation

growing from the cracks in its walls. Ravi and Khaja waited inside the abandoned house for Hari. It was nearing noon.

Footsteps neared, the blue boltless door creaked open and Hari came in.

'Here,' he said, 'these are all I could find.'

Four half-burnt beedis lay on his open palm. Ravi's eyes narrowed.

'You didn't check well,' Ravi said.

'I did all right. All along the road.'

'Before the tea shop?'

'No.'

'Why?'

'It was open.'

'At this time of day?'

'They were cleaning up. Not yet selling tea. That'll be in the evening.'

'OK,' Ravi said, quite satisfied with his interrogation. He was the eldest among the three. He was eleven, studying in eighth standard - two years senior to the other two both by age and in school. Residents of the same colony, they were thick as thieves.

Presently Khaja fished out a match box from his pocket - his contribution. Each pressed a beedi between his lips. Matchsticks struck and they fell to smoking. Only Hari could inhale the smoke deep into his lungs without falling into a nasty coughing fit. Others just sucked into their mouths and blew out.

Soon the half-beedis exhausted. Ravi felt they hadn't had it to satisfaction because it was about half their regular quota. All thanks to the tea shop, a real gold-mine, being open at this odd hour. Almost all elders of the area that smoked seemed to enjoy a cup of steaming tea along. Apparently it gave them greater pleasure. Naturally that's where you would find the stubs of beedis and, on lucky occasions, even cigarettes. Those found along the road were just add-ons.

'Damn that owner,' Khaja said. The use of the cuss word gave him a thrill. Even though they were by themselves he didn't dare say the f-word, which would've thrilled him all the more.

'Yes, damn him.'

Ravi reached into his pocket and took out a half-rupee coin. 'Any one's got any more? No? Damn you.'

'Damn you too.'

They must think up an idea. They would get two beedis, two full beedis for that much. But where would they buy? Every shopman in that area knew their fathers. Besides Khaja's father had a shop himself, although it was just a small wooden contraption standing in front of their hut just off the road. It didn't sell many. It couldn't contain many things. He sat before the shop on a wooden stool under the shade of the door that opened upwards vertically on its hinges. That little source of income had come to be the only one for Khaja's family. His father had been a labourer before his heart grew weak and the doctor advised against hard labour.

Suddenly Hari's eyes brightened up.

'You will be sitting at your shop after lunch, won't you, to replace your father?'

'Yes,' Khaja said warily, and added, 'but he will eat and come right away to send me off. He doesn't rest.'

'More than enough time. We'll be watching your shop. We'll meet you right away. Won't take time.'

They didn't wait for his consent. After a quick scan around the area for any inquisitive eyes and finding none, they left the building. Before dispersing, they plucked guava leaves and chewed on them to expel the smell of beedis.

Khaja quickly bolted down his lunch, relieved his father at the shop. He tried to calm his racing heart. He didn't want them to come to the shop. His father would skin him alive if he was caught out. 'Thank God the idiots didn't hand me the coin to get those beedis all by myself,' he thought. Which would've been a better idea but this meant only he would be at risk. That's why he didn't bring it up before those thick-heads.

From the stool he could see his sister washing clothes on the cemented platform next to the shop. She would surely tell on him.

Ravi and Hari could be seen walking towards the shop. He tried to look away. He was sweating profusely now.

'Four toffees, please,' Ravi said with a mischievous grin that stretched across his face almost from ear to ear.

Khaja hurriedly took out two beedis from the pack and thrust into Ravi's hand, all the while watching his sister. Luckily she was absorbed in her job.

'You gave two only, give us two more, please.' Ravi said.

Khaja quickly obliged.

He heaved a sigh of relief as his friends went away triumphant. Then he rounded his lips and attempted to whistle - a newly acquired passion - but in vain: he ended up hissing like a snake.

'What is it?' she said.

'Nothing, just felt like slapping you.'

His father took a little nap after lunch, and returned in a half hour to free him.

'Narrow escape!' said Khaja as he found the others in the run-down building. 'You went and Father came. Sister also grew suspicious.'

They smoked. Ravi and Khaja gave a try at a draught deep into their lungs but ended up as usual in a fit of breathless coughing. On their way back home, they plucked their mouth fresheners and chewed on them.

Khaja got home, did his homework for the next hour, ate his evening snack: idlis made from batter left over in the morning.

Slowly however, towards nightfall, an uncomfortable feeling came to settle over him and it kept nagging him until he went to bed. When tiredness enveloped him in a haze and he sank into the depths of sleep, it had transformed itself into his father, whom he saw sitting on the wooden stool before their little shop. He looked much much older with his crinkled face, sagging person. The old man looked at Khaja, who was standing near the platform. The old man's eyes were dilated and bloodshot. Khaja saw tears fill those blood-red eyes and trickle down his expressionless face.

He woke up with a start to find every one sleeping. He wiped tears from his eyes and tried to sleep.

Next day was Monday. When he and his sister were ready for school, Khaja demanded half a rupee of his mother.

'What for, I don't have any money. Take something from the shop to eat in the interval.'

'I want money. They sell Rasna there. I'll eat that.'

They concocted a tangy, orange coloured mix and froze it after sealing it in transparent pouches to call it Rasna.

His mother grumbled, glared at him for a second but eventually unknotted her saree end and looked for coin of the requested denomination.

During the interval, he held himself against the tempting Rasna among other delicacies the shop in front of their school boasted.

Ravi came up to him and asked, 'Got any money?'

Khaja said he didn't, but he could feel the coin in his shorts' pocket.

'Come let's eat Rasna. I've got a half-rupee.'

They got the icy Rasna split in two, because it was a half rupee apiece, and ate with great relish.

When Khaja came back home for lunch, he waited to be alone at the shop. When the chance presented itself, he softly laid the coin in the cashbox, taking care it didn't make that jangling sound.

growing from the cracks in its walls. Ravi and Khaja waited inside the abandoned house for Hari. It was nearing noon.

Footsteps neared, the blue boltless door creaked open and Hari came in.

'Here,' he said, 'these are all I could find.'

Four half-burnt beedis lay on his open palm. Ravi's eyes narrowed.

'You didn't check well,' Ravi said.

'I did all right. All along the road.'

'Before the tea shop?'

'No.'

'Why?'

'It was open.'

'At this time of day?'

'They were cleaning up. Not yet selling tea. That'll be in the evening.'

'OK,' Ravi said, quite satisfied with his interrogation. He was the eldest among the three. He was eleven, studying in eighth standard - two years senior to the other two both by age and in school. Residents of the same colony, they were thick as thieves.

Presently Khaja fished out a match box from his pocket - his contribution. Each pressed a beedi between his lips. Matchsticks struck and they fell to smoking. Only Hari could inhale the smoke deep into his lungs without falling into a nasty coughing fit. Others just sucked into their mouths and blew out.

Soon the half-beedis exhausted. Ravi felt they hadn't had it to satisfaction because it was about half their regular quota. All thanks to the tea shop, a real gold-mine, being open at this odd hour. Almost all elders of the area that smoked seemed to enjoy a cup of steaming tea along. Apparently it gave them greater pleasure. Naturally that's where you would find the stubs of beedis and, on lucky occasions, even cigarettes. Those found along the road were just add-ons.

'Damn that owner,' Khaja said. The use of the cuss word gave him a thrill. Even though they were by themselves he didn't dare say the f-word, which would've thrilled him all the more.

'Yes, damn him.'

Ravi reached into his pocket and took out a half-rupee coin. 'Any one's got any more? No? Damn you.'

'Damn you too.'

They must think up an idea. They would get two beedis, two full beedis for that much. But where would they buy? Every shopman in that area knew their fathers. Besides Khaja's father had a shop himself, although it was just a small wooden contraption standing in front of their hut just off the road. It didn't sell many. It couldn't contain many things. He sat before the shop on a wooden stool under the shade of the door that opened upwards vertically on its hinges. That little source of income had come to be the only one for Khaja's family. His father had been a labourer before his heart grew weak and the doctor advised against hard labour.

Suddenly Hari's eyes brightened up.

'You will be sitting at your shop after lunch, won't you, to replace your father?'

'Yes,' Khaja said warily, and added, 'but he will eat and come right away to send me off. He doesn't rest.'

'More than enough time. We'll be watching your shop. We'll meet you right away. Won't take time.'

They didn't wait for his consent. After a quick scan around the area for any inquisitive eyes and finding none, they left the building. Before dispersing, they plucked guava leaves and chewed on them to expel the smell of beedis.

Khaja quickly bolted down his lunch, relieved his father at the shop. He tried to calm his racing heart. He didn't want them to come to the shop. His father would skin him alive if he was caught out. 'Thank God the idiots didn't hand me the coin to get those beedis all by myself,' he thought. Which would've been a better idea but this meant only he would be at risk. That's why he didn't bring it up before those thick-heads.

From the stool he could see his sister washing clothes on the cemented platform next to the shop. She would surely tell on him.

Ravi and Hari could be seen walking towards the shop. He tried to look away. He was sweating profusely now.

'Four toffees, please,' Ravi said with a mischievous grin that stretched across his face almost from ear to ear.

Khaja hurriedly took out two beedis from the pack and thrust into Ravi's hand, all the while watching his sister. Luckily she was absorbed in her job.

'You gave two only, give us two more, please.' Ravi said.

Khaja quickly obliged.

He heaved a sigh of relief as his friends went away triumphant. Then he rounded his lips and attempted to whistle - a newly acquired passion - but in vain: he ended up hissing like a snake.

'What is it?' she said.

'Nothing, just felt like slapping you.'

His father took a little nap after lunch, and returned in a half hour to free him.

'Narrow escape!' said Khaja as he found the others in the run-down building. 'You went and Father came. Sister also grew suspicious.'

They smoked. Ravi and Khaja gave a try at a draught deep into their lungs but ended up as usual in a fit of breathless coughing. On their way back home, they plucked their mouth fresheners and chewed on them.

Khaja got home, did his homework for the next hour, ate his evening snack: idlis made from batter left over in the morning.

Slowly however, towards nightfall, an uncomfortable feeling came to settle over him and it kept nagging him until he went to bed. When tiredness enveloped him in a haze and he sank into the depths of sleep, it had transformed itself into his father, whom he saw sitting on the wooden stool before their little shop. He looked much much older with his crinkled face, sagging person. The old man looked at Khaja, who was standing near the platform. The old man's eyes were dilated and bloodshot. Khaja saw tears fill those blood-red eyes and trickle down his expressionless face.

He woke up with a start to find every one sleeping. He wiped tears from his eyes and tried to sleep.

Next day was Monday. When he and his sister were ready for school, Khaja demanded half a rupee of his mother.

'What for, I don't have any money. Take something from the shop to eat in the interval.'

'I want money. They sell Rasna there. I'll eat that.'

They concocted a tangy, orange coloured mix and froze it after sealing it in transparent pouches to call it Rasna.

His mother grumbled, glared at him for a second but eventually unknotted her saree end and looked for coin of the requested denomination.

During the interval, he held himself against the tempting Rasna among other delicacies the shop in front of their school boasted.

Ravi came up to him and asked, 'Got any money?'

Khaja said he didn't, but he could feel the coin in his shorts' pocket.

'Come let's eat Rasna. I've got a half-rupee.'

They got the icy Rasna split in two, because it was a half rupee apiece, and ate with great relish.

When Khaja came back home for lunch, he waited to be alone at the shop. When the chance presented itself, he softly laid the coin in the cashbox, taking care it didn't make that jangling sound.